Information technology bends toward speed

We have this idea that people used to be worried about quality, and it’s only recently that we’ve all been poisoned by consumer culture into valuing speed and ease above all else. Information technologies, though, have been making tradeoffs in favor of speed since the beginning of recorded history. Clay tablets were a remarkably durable book format. Even now, more than 3000 years later, we have at least 500,000 tablets and fragments in museums worldwide – for a technology that went extinct in the first century BC. By contrast, we have about the same number of books that were printed between 1455 and 1500.1 1 Around 550,00 incunabula, or books from the first stages of printing in Europe, survive. Granted, each printed book represents more information than a clay tablet fragment, and clay tablets were in use for several thousand years, but it’s astonishing that tablets are not rarer.

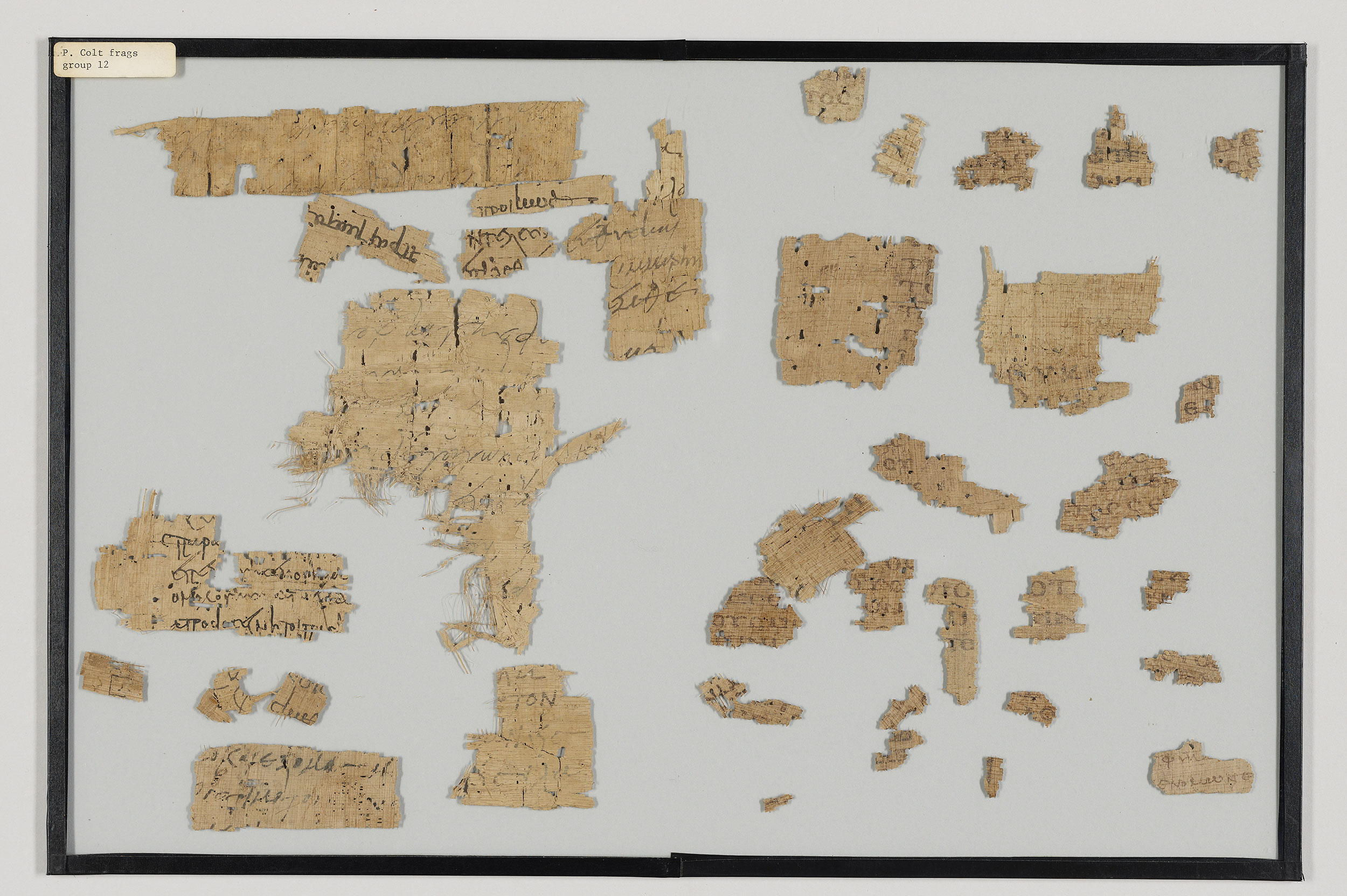

Papyrus scrolls supplanted clay tablets because alphabetic writing was much faster and easier to learn, but curving scripts can’t be written in clay. Because information technologies travel together, to get the alphabet, writers adopted papyrus as well. By contrast, even though they are newer, extant papyrus scrolls are much rarer than clay tablets. They’re made of organic materials –specifically a wetland sedge that only grew in the Nile river valley– and as such, they burn, wash away, break apart, rot, and even get eaten by pests.

Papyrus scrolls are worse in a number of ways (less durable and harder to make, for a start), but they made the process of writing faster. We made that tradeoff, and we’ve kept doing it ever since.

References

Colt Papyrus Fragment 12, The Morgan Library and Museum.

Frederick G. Kilgour. The evolution of the book . Oxford University Press. 1998.

Notes mentioning this note

<blockquote class = “epigraph”>”Two basic systems: Development and Maintenance. The sourball of every revolution: after the revolution, who’s going to...